March was the hottest in India since records began 122 years ago and in Pakistan, the highest worldwide positive temperature anomaly during March was recorded and many individual weather stations recorded monthly all-time highs through March. At the same time, March was extremely dry, with 62 percent less than normal rainfall reported over Pakistan and 71 percent below normal over India, making the conditions favourable for local heating from the land surface. The heatwave continued over the month of April and reached its preliminary peak towards the end of the month. By the 29th of April, 70 percent of India was affected by the heatwave.

While heatwaves are not uncommon in the season preceding the monsoon, the very high temperatures so early in the year coupled with much less than average rain have led to extreme heat conditions with devastating consequences for public health and agriculture. The full health and economic fallout, and cascading effects from the current heat wave will however take months to determine, including the number of excess deaths, hospitalisations, lost wages, missed school days, and diminished working hours. Early reports indicate 90 deaths in India and Pakistan, and an estimated 10-35 percent reduction in crop yields in Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, and Punjab due to the heatwave.

The early and prolonged heat particularly affected the North West of India and Southern parts of Pakistan, the so-called bread basket of the subcontinent. Towards the end of April and in May the heatwave also reached more coastal areas and the Eastern parts of India. It was however the early, prolonged and dry heat that made this event stand out as distinct from heatwaves occurring earlier this century.

Scientists from India, Pakistan, the Netherlands, France, Switzerland, New Zealand, Denmark, United States of America and the United Kingdom, collaborated to assess to what extent human-induced climate change altered the likelihood and intensity of the heatwave.

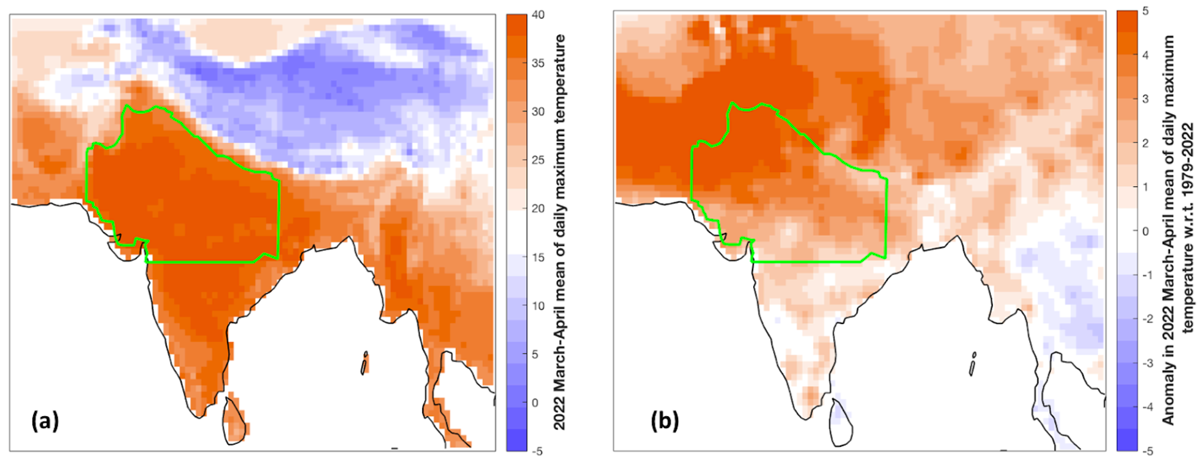

Using published peer-reviewed methods, we analysed how human-induced climate change affected the heat in the early affected region (see fig. 1) that also experienced a lot less rain than usual. To capture the duration of the event we chose the March-April average of daily maximum temperatures.

Main findings

- The 2022 heatwave is estimated to have led to at least 90 deaths across India and Pakistan, and to have triggered an extreme Glacial Lake Outburst Flood in northern Pakistan and forest fires in India. The heat reduced India’s wheat crop yields, causing the government to reverse an earlier plan to supplement the global wheat supply that has been impacted by the war in Ukraine. In India, a shortage of coal led to power outages that limited access to cooling, compounding health impacts and forcing millions of people to use coping mechanisms such as limiting activity to the early morning and evening.

- Gridded observations that correspond well to station data and capture India and Pakistan are comparably short (starting 1979). The exact return period of such a rare event is thus highly uncertain and depends on the length of the data as well as the fitted distribution. When combining information of the shorter dataset with a dataset that only covers India but for a longer time span (starting 1951) we estimate the return period to be around 100 years in today’s climate of 1.2C global warming. We thus use 1 in 100 years, as the event definition for the attribution study.

- To increase the data available and determine the role of climate change in the observed changes we combine observations with 20 climate models and we conclude that human-caused climate change made this heatwave hotter and more likely.

- Because of climate change, the probability of an event such as that in 2022 has increased by a factor of about 30.

- The same event would have been about 1C cooler in a preindustrial climate.

- With future global warming, heatwaves like this will become even more common and hotter. At the global mean temperature scenario of +2C such a heatwave would become an additional factor of 2-20 more likely and 0.5-1.5C hotter compared to 2022.

- We note here that our results are likely conservative; the relatively short lengths of observed data rendered it difficult to consider statistical fits that are more ideal for extremes. In large model ensembles more accurate fits indicate a larger increase in likelihood.

- It is important to note that this early heatwave was accompanied by much below average rainfall and humidity and thus constituted a dry heatwave, rendering humidity much less important for health impacts than heatwaves occurring late in the season and in coastal areas.

- In Pakistan and India, extreme heat hits hardest for people who must go outside to earn a daily wage (e.g. street vendors, construction and farm workers, traffic police), and consequently lack access to consistent electricity and cooling at home, limiting their options to cope with prolonged heat stress.

- Rising temperatures from more intense and frequent heat waves will render coping mechanisms inadequate as conditions in some regions meet and exceed limits to human survivability. Mitigating further warming is essential to avoid loss of life and livelihood.

- While some losses will inevitably occur due to the extreme heat, it is misleading to assume that the impacts are inevitable. Adaptation to extreme heat can be effective at reducing mortality. Heat Action Plans that include early warning and early action, awareness raising and behaviour changing messaging, and supportive public services can reduce mortality, and India’s rollout of these has been remarkable, now covering 130 cities and towns.