In this arid region, a large part of the population depends on rain-fed agriculture, in particular wheat farming and livestock. While there is a comparably large variability in the year to year rain, this drought was the second worst in the observed record, driven by rising temperatures. It hit at a time when other socio-economic factors including the ongoing war in Ukraine with its impacts on energy and food prices, as well as conflicts and political unrest, compound the consequences of the drought.

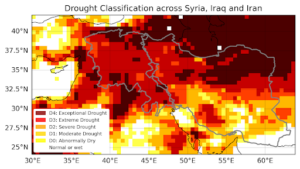

Scientists from Iran, the Netherlands, the UK and the US used published peer-reviewed methods to assess whether and to what extent climate change influenced the 3-year drought in two regions: (1) the fertile crescent around the Euphrates and Tigris rivers, encompassing large parts of Iraq and Syria and (2) Iran. There are several ways to characterise a drought: meteorological drought considers only low rainfall, while agricultural drought combines rainfall estimates with evaporation. As increased evapotranspiration due to regional warming can play a major role in exacerbating drought impacts, we assess agricultural drought in this study. The main variable used to characterise the drought is the Standardised Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) which calculates the difference between rainfall and potential evapotranspiration to estimate the available water. The more negative the values are, the more severe the drought is classified. Figure 1 depicts the SPEI classification for the 36 months from July 2020 up to June 2023 over the two study regions.

Main findings

- The drought affects a region with a highly vulnerable population due to varying degrees of fragility and conflict including war and post-war transition, rapid urbanisation in the face of limited technical capacity, and regional instability. These dynamics increased vulnerability to the impacts of drought and created a humanitarian crisis.

- The whole Euphrates and Tigris basin (ET-basin) and large parts of Iran experienced extreme and exceptional agricultural drought over the 36 months up to June 2023, making it the second-worst drought on record in both regions based on SPEI.

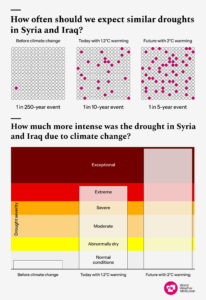

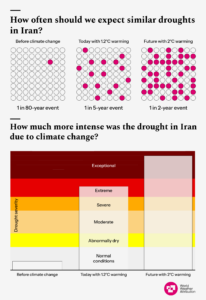

- The extreme nature of the drought is not rare in the present climate (which has been warmed by 1.2°C due to burning of fossil fuels). Events of comparable severity are expected to occur at least every decade.

- Using three different observations-based data products we find a strong trend towards more severe droughts in both regions. We find that the combination of low rainfall and high evapotranspiration as unusual as the recent conditions – that is, an event that occurred around every 5-10 years – in a world that had not been warmed 1.2°C would be so much less severe that nowadays it would not be classified as a drought at all.

- In order to identify whether and to what extent human-induced climate change was a driver of these trends we combine observations-based data products and climate models and look at the 36-month SPEI in both regions. We find that over the ET-basin the likelihood of such a drought occurring has increased by a factor of 25 compared to a 1.2°C cooler world. Over Iran the likelihood of such a drought occurring has increased by a factor of 16 compared to a 1.2°C cooler world.

- For both regions human-induced climate change has increased the intensity of such a drought such that it would not have been classified as a drought in a 1.2°C cooler world. Thus confirming that the observed finding is indeed caused by human-induced climate change.

- To understand the meteorological drivers behind this change in agricultural drought we also analysed rainfall and temperature separately and found there to be little change in the likelihood and intensity of rainfall but a very large increase in temperature. We thus conclude that this strong increase in drought severity is primarily driven by the very strong increase in extreme temperatures due to the burning of fossil fuels.

- Unless the world rapidly stops burning fossil fuels, these events will become even more common in the future. In a world 2°C warmer than preindustrial an event like this would be an exceptional drought, the worst category possible.

- The high levels of water stress in the region today are exacerbated by limitations in technical capacity, water management, and regional cooperation. Rapid population growth, industrialization and land-use changes, dam practices and river flow management between upstream and downstream countries, aged water treatment plants, and low efficiency of irrigation water systems have contributed to a complex water crisis. Water is moreover weaponised in conflict, with water systems increasingly targeted for sabotage.

- These results highlight that despite ‘low confidence’ in IPCC projections for drought in the region, increasing water stress driven by human-induced climate change as well as other systemic factors continues to be a major threat for the population and requires urgent efforts for more effective water management strategies, interdisciplinary humanitarian response, and regional cooperation that includes farmers and other stakeholders in the planning.