From Israel, Palestine, Lebanon and Syria, in the West, to Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam and the Philippines in the East, large regions of Asia experienced temperatures well above 40°C for many days. The heat was particularly difficult for people living in refugee camps and informal housing, as well as for outdoor workers.

Heatwaves are arguably the deadliest type of extreme weather event and while the death toll is often underreported, hundreds of deaths have been reported already in most of the affected countries, including Palestine, Bangladesh, India, Thailand, Myanmar, Cambodia and the Philippines. The heat also had a large impact on agriculture, causing crop damage and reduced yields, as well as on education, with holidays having to be extended and schools closed in several countries, affecting millions of students.

Extreme heat in South Asia during the pre-monsoon season is becoming more frequent. Two previous World Weather Attribution studies focused on extreme heat events in the region: the 2022 India and Pakistan heatwave and the 2023 humid heatwave that hit India, Bangladesh, Lao PDR and Thailand. Despite differences in the nature and impact of the events (drier heat in 2022 leading to widespread loss of harvest, and humid heat in 2023 with greater impacts on people), both studies found that human-induced climate change influenced the events, making them around 30 times more likely and much hotter.

Scientists from Lebanon, Sweden, Malaysia, the Netherlands, the United States and the United Kingdom collaborated to assess to what extent human-induced climate change altered the likelihood and intensity of the extreme heat in three Asian regions: 1) West Asia, including Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Palestine and Jordan; 2) the Philippines in East Asia; and 3) South and Southeast Asia, including India, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Lao PDR, Vietnam, Thailand and Cambodia.

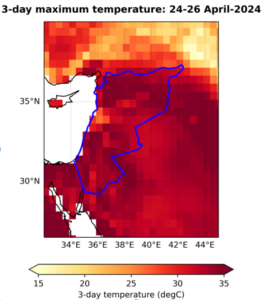

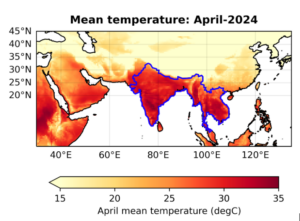

Using published peer-reviewed methods, the scientists analysed how human-induced climate change altered the likelihood and intensity of the 3-day April heatwave in West Asia and a 15-day April heatwave in the Philippines. Figure 1 shows these two regions, outlined in blue, while figure 2 shows the South Asia region. For this region, the analysis focused on observed weather data, but not climate models, as the affected region largely overlaps with the study areas of the previous studies. The observational data for the whole month of April confirmed that the role of climate change is likely of similar magnitude to the heatwaves studied in 2022 and 2023, and the results of a full attribution analysis would not be significantly different.

Main Findings

-

- The heatwave exacerbated already precarious conditions faced by internally displaced people, migrants and those in refugee camps and conflict zones across West Asia. In Gaza, extreme heat worsened the living conditions of 1.7 million displaced people. The heatwave added pressure to the many challenges already faced by people in refugee camps and conflict zones, such as water shortages, difficulties to access medicines and poor living conditions for the large population that lives in makeshift tents that trap heat. With limited institutional support and options to adapt, the heat increases health risks and hardship.

- The extreme heat has forced thousands of schools to close down in South and Southeast Asia. These regions have previously also incurred school lockdowns during COVID-19, increasing the education gap faced by children from low-income families, enhancing the risk of dropouts, and negatively impacts the development of human capital.

- Heat impacts certain groups like construction workers, transport drivers, farmers, fishermen etc. disproportionately. It both impacts their livelihoods and causes a reduction in income, and results in personal health risks.

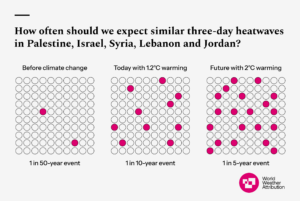

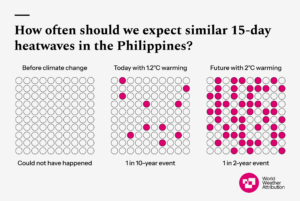

- In the current climate, warmed by 1.2°C since pre-industrial times due to human activities, this kind of extreme heat event is not very rare. In West Asia, the chance of it occurring in any given year is around 10% – or once every 10 years. In the Philippines, the chance of such an event happening in any given year is also around 10% – or once every 10 years under the current El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) conditions, and a 1-in-20 year event, overall, without the influence of El Niño. In the larger South Asia region, an extremely warm April such as this one is a somewhat rarer event, with a 3% probability of happening in a given year – or once every 30 years.

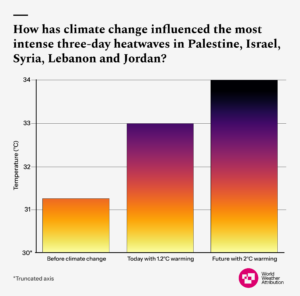

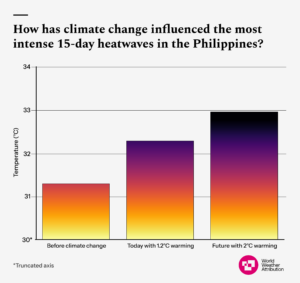

- To estimate the influence that human-caused climate change has had on extreme heat in West Asia and the Philippines, we combine climate models with observations. Observations and models both show a strong increase in likelihood and intensity. In the Philippines, the change in likelihood is so large that the event would have been impossible without human-caused climate change. In West Asia, climate change increased the probability of the event by about a factor of 5.

- In terms of intensity, we estimate that a heatwave such as this one in West Asia is today about 1.7°C warmer than it would have been without the burning of fossil fuels. In the Philippines the intensity increase due to human-induced climate change is about 1.2°C.

- We also look at the role of the ENSO. In the Philippines, we find that the current El Niño made the heatwave about 0.2°C hotter. In West Asia, on the other hand, we do not find any influence of ENSO in the event, which is consistent with previous research.

- If the world warms to 2°C above pre-industrial global mean temperatures, in both regions the likelihood of the extreme heat would increase further, by a factor of 2 in West Asia and 5 over the Philippines, while the temperatures will become another 1°C hotter in West Asia and 0.7°C hotter in the Philippines.

- In South Asia, a region that we have studied twice in the last two years, our analysis was simpler and based only on observations. Similarly to what we found in previous studies, we observe a strong climate change signal in the 2024 April mean temperature. We find that these extreme temperatures are now about 45 times more likely and 0.85ºC hotter. These results align with our previous studies, where we found that climate change made the extreme heat about 30 times more likely and 1ºC hotter.

- Existing heatwave action plans and strategies are challenged by rapidly growing cities, increase in informal settlements and exposed populations, reduction in green spaces and rise in energy demands. While many cities have been implementing solutions like cool roofs, nature based infrastructure design, and adherence to climate risk informed building codes, there is limited focus on retrofitting and upgrading of existing buildings and settlements, with infrastructure deficits (e.g. asbestos roofs), to make them more liveable.

- Some countries such as India have comprehensive heat action plans in place, yet to protect some of the most vulnerable people, these must be expanded with mandatory regulations, such as workplace interventions for all workers to address heat stress, such as scheduled rest breaks, fixed work hours, and rest-shade-rehydrate programs (RSH) are necessary, but yet to become part of worker protection guidelines in the affected regions.

- The recurrent heat events and associated impacts every year in these regions in the past few years have enabled heatwaves to be recognised as a serious hazard of concern in most countries, with proper guidelines and action plans in place. At the same time, cross-sectoral collaborative strategies that focus on providing immediate relief during the hot days are needed.