On Saturday, November 16, 2024, Super Typhoon Man-Yi made landfall in the Philippines with maximum sustained winds of 195 km/h, capping an unprecedented month of extreme weather. It was the 24th named storm of the season and the sixth typhoon to strike the Philippines within just 30 days. Typically, November sees only three named storms in the entire basin, with one reaching super typhoon status, based on historical averages (NASA, 2024).

The Japan Meteorological Agency confirmed that November 2024 also set a record for the simultaneous occurrence of four named storms in the Pacific basin, the most since records began in 1951. The onslaught began with Tropical Cyclone (TC) Trami in late October, which killed more than a dozen people and unleashed a month’s worth of rain on the northern Philippines. This was followed by Super Typhoon Kong-Rey, which passed to the north of the Philippines before making landfall in Taiwan and killing at least three people. Next, Typhoon Xinying slammed Luzon with winds of 240 km/h, forcing the evacuation of 160,000 people, while Typhoons Toraji and Super Typhoon Usagi brought a three-meter storm surge and torrential rain (BBC, 2024; ACT Alliance, 2024).

The compounding effects of the series of storms caused severe damage to infrastructure, with early estimates of economic losses of nearly half a billion USD (NDRRMC, 2024). Trami and Kong-Rey alone killed more than 160 people, displaced more than 600,000, and impacted over 9 million individuals across the region (ACT Alliance, 2024).

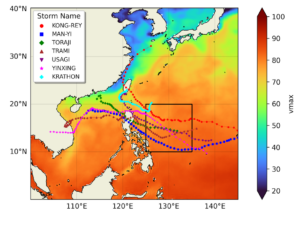

Having assessed the role of climate change in individual tropical cyclones, such as Typhoon Geami and Hurricane Helene, scientists from the Philippines, the United Kingdom and the Netherlands have collaborated this time to assess whether and to what extent climate change influenced the sequence of TCs affecting the Northern Philippines. In order to do this we focus on two measures: (1) The potential intensity (PI, the theoretical maximum wind speed based on the atmospheric and ocean conditions relevant to TC development) during the months of September to November and (2) changes in the rate of landfalling major TCs, assessed using a stochastic model of storm tracks and intensities. Figure 1 shows the potential intensity for the September-November season, the region of analysis outlined in black and the cyclone tracks of the typhoons hitting the Philippines.

Main findings

- The six consecutive typhoons that impacted northern Luzon between late October and November highlight the challenges of adapting to back-to-back extreme weather events. With 13 million people impacted and some areas hit at least three times, repeated storms have created a constant state of insecurity, worsening the region’s vulnerability and exposure.

- The six typhoons impacted Luzon Island, which is comparably affluent, especially in the northern and central regions. Despite having the country’s lowest household poverty rates, cities on the island remain highly vulnerable to flooding, particularly due to urban sprawl, river silting, and deforestation.

- To assess if human-induced climate change influenced the environmental conditions leading to the high number of storms, we first determine if there is a trend in the observation-based estimates of potential intensity. Our best estimate is that the observed potential intensity has become about 7 times more likely and the maximum intensity of a potential typhoon has increased by about 4 m/s (14.5 km/h).

- To quantify the role of human-induced climate change we also analyse climate models. The change in potential intensity attributable to human-induced climate change is smaller in the models than in the observations. When combining both, we find that the potential intensity as observed in 2024 has been made more likely by a factor of about 1.7, due to warming caused primarily by the burning of fossil fuels. The intensity has increased by about 2 m/s (7.2 km/h). These changes are projected to increase with further warming, meaning that in a 2.6°C warmer world the expected increase is another 2 m/s: this reflects projected conditions by the end of the century given currently implemented policies. As all models significantly underestimate the observed change, these numbers are assumed to be a conservative estimate of the role of climate change.

- Of the six major storms that affected the Philippines in late October-mid November 2024, three made landfall as major typhoons (defined as category 3 or above). We therefore also assess whether climate change has increased the odds of at least three major typhoons making landfall in the Philippines in a year. Using a statistical model we find that in today’s climate, warmed by 1.3°C, such an event is expected once every 15 (6.5-45) years. That is 25% more frequent than it would have been had we not burned fossil fuels. In a 2°C warmer climate from pre-industrial times we expect at least 3 major typhoons hitting in a single year every 12 years (best estimate).

- For six storms to impact the northern Philippines in such a short period is extremely unusual, and it is difficult to study such an event directly because it is so rare. Overall, our results show that conditions conducive to the development of consecutive typhoons in this region have been enhanced by global warming, and the chance of multiple major typhoons making landfall will continue to increase as long as we continue to burn fossil fuels.

- The series of typhoons is one of several examples of consecutive events observed this year, for example floods in the Sahel Zone, and hurricanes Helene and Milton. Such consecutive extreme events make it difficult for populations to recover. Given the likelihood of compounding events will increase as the climate warms, it is crucial that communities take steps to become more resilient to extreme weather.

- The Philippines is advancing a proactive disaster risk management framework, highlighted by proposed legislation to formalize anticipatory action through a State of Imminent Disaster, enabling preemptive resource allocation. This innovative approach complements robust emergency responses. However, consecutive typhoons have underscored the extraordinary challenge of ensuring continuity and resilience amidst escalating climate risks.