At the time of writing, the fires are not fully contained and other fires have emerged in the San Diego area (CNN, 2025), and the full extent of the destruction will only become apparent over the coming weeks and months. To date at least 28 people are known to have lost their lives and more than 16,000 structures have been destroyed (CAL FIRE).

Coastal Southern California has a Mediterranean climate with fire-adapted chaparral shrubland, grasses, and oak trees. Wildfire is a natural part of the local ecosystem, with some species even depending on it. Wildfires are typically largest from July to September due to low fuel moisture caused by lack of precipitation in summer, high temperatures, and low humidity. However, some of the region’s most destructive events occur in fall or early winter due to the arrival of the Santa Ana windy season.

This particular event stands out due to the speed of fire spread and the challenge of suppressing it due to exceptionally strong Santa Ana winds. These dry winds occur in Coastal Southern California when air flows toward the coast from inland mountains. These winds typically happen in the cooler months from October-March, as cooling over the Great Basin leads to the formation of a high-pressure system (Abatzoglou et al., 2013). This type of synoptic circulation pattern was observed at the start of the fires and the 7th and 8th January 2025, and was strengthened by a mid-troposphere “cut-off-low” weather system that came off the higher-latitude jet stream and traveled to Baja California.

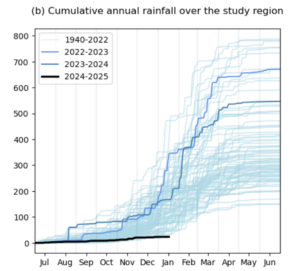

The typical seasonal arrival of rainfall from October-December typically marks the end of the wildfire season, nullifying the ability of Santa Ana winds to easily spread large and intense fires. However, the region has not experienced significant rainfall since May 2024, meaning grasses and brush were dry and highly flammable when the fires broke out. Additionally, above-average precipitation in winters of 2022/23 and 2023/24 had previously encouraged vegetation growth, providing more fuel for the fires.

Human-induced climate change is increasing wildfires in many regions of the world, as hot, dry and windy weather conditions increase the risk of fires both starting and spreading. Researchers from the United States, the Netherlands, Denmark, Belgium, France, Sweden and the United Kingdom collaborated to assess to what extent human-induced climate change altered the likelihood and intensity of the weather conditions that fuelled the LA wildfires, and how the conditions will be affected with further warming.

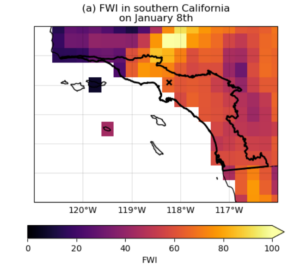

To analyse the fire weather conditions we used the Fire Weather Index (FWI), which uses meteorological information (temperature, humidity, wind speed and precipitation over the preceding weeks and days) to characterise the weather conditions making wildfire more likely. We focus on the day of the highest index associated with the enormous, fast spread of the fires in the ecological region surrounding Los Angeles, indicated by the red outline in Figure 1. We also analyse the drought conditions in October-December, a time that usually brings rain to the region, but was almost completely dry this year, providing ample fuel for the fires and thus contributing to the extent and spread (Figure 2). We specifically analyse the drought end-date, defined as the number of days after the 1st of September on which the greatest absolute 7-day drop in the drought code occurs. As another line of evidence we also study changes in circulation patterns, focusing on trends in the occurrence of atmospheric patterns known to be associated with enhanced fire risk. Using observations since 1950, we identify similar atmospheric patterns from December to February (1950–2023) within the region and assess whether there is a trend. In addition, we analyse simulations from process-based fire models run under factual and counterfactual climate conditions, to understand what the expected effect of climate change is on fire extent in the region.

Main Findings

- Coastal Southern California is an environment highly prone to catastrophic wildfires. The destructiveness of a fire thus also strongly depends not only on the weather conditions but also on whether land use and fire management strategies take these characteristics into account. The Palisades Fire occurred in an officially designated Very High Fire Hazard Severity Zone, while the Eaton Fire was only partly within such an area. This means fire risk has always been very high and building regulations require at least 200 ft of vegetation management around structures within the designated Very High Fire Hazard Severity Zones. Post-fire assessments will check compliance with these requirements.

- Looking at weather observations, in today’s climate with 1.3°C global warming relative to preindustrial, the extreme Fire Weather Index (FWI) conditions that drove the LA fires are expected to occur on average once in 17 years. Compared to a 1.3°C cooler climate this is an increase in likelihood of about 35% and an increase in the intensity of the FWI of about 6%. This trend is however not linear, with high FWI conditions increasing faster in recent decades.

- To determine the role of climate change in this observed trend we combine the observation-based estimates with climate models. Eight of the eleven models examined also show an increase in extreme January FWI, increasing our confidence that climate change is driving this trend. Combining models and observations, we find that human-induced warming from burning fossil fuels made the peak January FWI more intense, with an estimated 6% increase in intensity, and 35% more probable. Fire weather indices consist of many variables, which are not always well represented by climate models. Wind, in particular, is often poorly represented. While we have high confidence in the qualitative change, that the likelihood and intensity of the FWI has increased due to human-induced climate change, the precise numbers have a wide range of uncertainty due to the model performance.

- This trend is projected to continue into the future, with peak FWI intensifying by a further 3% and similar values becoming a further 35% more likely if the world warms to 2.6°C, which is the lowest warming expected under current policies by 2100.

- We also assess the drought conditions leading up to the fires, using two different indices. First, we consider the October-December (OND) standardised precipitation index, which is defined relative to the 1991-2020 climatology and measures how dry OND 2024 was in comparison. We calculated the index for today’s climate of 2024 and a 1.3° colder climate. Similarly dry seasons are expected to occur on average once every 20 years in the current climate; this is 2.4 times more likely than in a preindustrial climate. The OND ENSO conditions also increased the likelihood of the drought by a factor of 1.8 relative to neutral ENSO conditions. Climate models do not agree on the direction of precipitation trends in this region, so we are unable to formally attribute this change to global warming.

- We further assess changes in the timing of the end of the dry season. Analysing observations, we find that the length of the dry season has increased by about 23 days since the global climate was 1.3°C cooler. This means that, due to the burning of fossil fuels, the dry season, when a lot of fuel is available, and the Santa Ana winds, that are crucial for the initial spread of wildfires, are increasingly overlapping.

- Our observational analysis shows that the frequency of an atmospheric circulation pattern such as that of January 8th 2025, which is known to strengthen Santa Ana wind events, has increased in winter, raising the risk of weather conditions that drive the spread of wildfire. Whether this trend is attributable to human-caused climate change requires a more in depth study of the patterns in observations and climate models.

- As an additional line of evidence, we analyse simulations from process-based fire models run under observed and counterfactual climate conditions, to estimate the expected effect of climate change on burned area in the region. These models suggest that the potential burned area in December-January in the Los Angeles area is today substantially higher than it would be in the absence of climate change. We note that these models represent changes in potential burned area driven by climate change but do not faithfully reproduce observed trends in burned area, and any real-world changes are the combined result of climate change and direct human interventions in the landscape.

- The Coastal Southern California region is a small area, often represented by only a few grid-boxes in climate models and gridded observational products. Furthermore, the complexity of the weather conditions characterising fire weather and large year to year variability in rainfall means that precise numbers in every single line of evidence are uncertain. However, the lines of evidence examined overall point in the same direction, indicating that conditions that make extreme fires more likely are increasing. This is also in line with existing literature, as summarised by the IPCC (AR6 WGI, Chapter 12), that shows an increase in high temperatures, combined with a drying in the larger area and thus higher fire risk. Given all these lines of evidence we have high confidence that human-induced climate change, primarily driven by the burning of fossil fuels, increased the likelihood of the devastating LA fires.

- The elderly, people living with disability (especially limited mobility), lower-income people without personal vehicles, and population groups that received late warnings were disproportionately impacted, as they had a more difficult time getting to safety. The neighborhood of Altadena with a large Black population was in the path of the fires, which destroyed the major source of generational wealth for many residents who had previously faced discriminatory redlining practices.

- The wildfires exposed critical weaknesses in the city’s water infrastructure, designed for routine fires rather than the extreme demands of large-scale fires. The crisis highlighted the need for strategic investments in resilient water systems and improved pressure management, alongside stronger climate adaptation and emergency preparedness measures to address more frequent future wildfires.