On 7 March, 2025, Bahía Blanca, Argentina, experienced an unprecedented rainfall event with over 300 mm of rain in just 8 hours, nearly half of the city’s annual average. This extreme event, the heaviest in the city’s recorded history (1956-present), was caused by a cold front reaching the area after several days of hot, humid weather. A week earlier, Bahía Blanca had already received more than 80 mm of rain, which may have contributed to soil saturation before the flooding. A larger region, including the capital Buenos Aires, had been experiencing extreme heat since mid-February, with temperatures exceeding 40°C in northern Argentina, southern Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay. Between 19 February and 8 March 2025, 61 cities in central-north Argentina recorded heatwave conditions.

The extreme rainfall on March 7th affected over 300,000 people, with 16 reported deaths, 1,400 being displaced (A24, 2025) and two persons still missing (La Nación, 2025). The damage estimated in the city amounts to 400 million USD (Ámbito, 2025). At the same time, heat alerts were issued in 15 provinces, with record temperatures in the north (Buenos Aires Herald, 2025, SMN Argentina via X). Buenos Aires faced blackouts and traffic disruptions affecting hundreds of thousands due to peak energy demand (Global Times, 2025, AP News, 2025). While no data on heat-related mortality is available at the time of writing, past events have shown increased mortality risks associated with events like this (Chesini et al., 2019; Chesini et al., 2021, Pinotti et al., 2024).

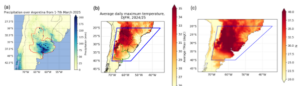

To assess to what extent human-induced climate change altered the likelihood and intensity of the heavy precipitation leading to the severe flooding, as well as the extreme heat researchers from Argentina, Kenya, the Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark, Mexico, the United States and the UK undertook an attribution study for the extreme rainfall in the most affected region, that coincides with the area where flood warnings were in place (Fig. 1a), as well as for the extreme seasonal heat in the wider area (Fig. 1b). For this larger region we further calculate the heat index, a combination of high temperatures and humidity to assess the role of climate change in the heatwave directly preceding the extreme rainfall (Fig. 1c). In Argentina, the impacted areas were affected by rainfall that occurred intermittently between 1-7 March. We therefore studied changes in the wettest 7-day period over the study region. The heat was especially intense in February and March, but early hot spells since January resulted in the entire season being exceptionally warm which is important for understanding the overall impacts, so we focus on the summer season (December to March) for the temporal definition of the heat event.

Figure: (a): 7-day accumulated rainfall during 1-7 March 2025, based on MSWEP data. The study region is highlighted in red. The scatter plots show the rainfall accumulations for the same period from 25 weather stations by the National Weather Services (NWS). (b) The average of daily maximum temperature during 1 Dec 2025 -18 March 2025, based on MSWX dataset. The study region (SouthEast South America domain or the SES domain) is highlighted in blue. (c) Average Heat index (HI) during 15 Feb-7 March, 2025, based on ERA5 dataset. The blue highlight shows the SES domain.

Main findings

- In Northern Argentina, including the Buenos Aires province and CABA, intensified and more frequent extreme heat and heavy rainfall events as well as simultaneous or sequential extremes like heat-heavy rainfall or hot-dry events heighten the risk of compounding hydrometeorological hazards. CABA’s aging population, urban development, and high population density increase both exposure and vulnerability to these hazards.

- Almost 50% of the urban population is employed in the informal economy and a large proportion of the urban livelihoods are sensitive to climate shocks e.g. due to employment disruption and exposure to heat.

- Based on gridded reanalysis products, we find that the extreme heat event is relatively rare, expected to occur in today’s climate about once every 50 to 100 years. However, in a 1.3°C cooler climate, extreme heat such as observed in the summer 2024/25 would have been virtually impossible. When repeating the analysis for the shorter hot and humid heat wave directly preceding the rainfall event, we find a similarly large role of human-induced climate change.

- Climate models also show that climate change is making such temperatures much more frequent and intense. However, the increase in the models is smaller than in reanalysis products and thus likely underestimating the effect of climate change. Nevertheless, looking at the future, models show a very strong trend that increases with future warming, rendering such an event a common occurrence in a 2.6°C warmer climate compared to pre-industrial.

- The influence of climate change on the rainfall event is much less clear. While all of the 35 available weather stations in the area show an increase in the intensity of heavy rainfall of between 7-30% associated with global warming of 1.3°C, this is not represented in any of the available gridded reanalysis products which show on average a decreasing trend.

- Climate models are largely in agreement with the station data and on average show an increase in the likelihood and intensity of heavy rainfall such as observed in early March. A similar increase in most, but not all, models is seen for an additional 1.3°C warming, representing a 2.6°C climate.

- Station data and model data both show an increasing trend in extreme rainfall with rising temperatures, which is also what is expected for rainfall events of this kind in a warming climate. Thus, it is likely that climate change increased the likelihood and intensity of the heavy rainfall. However as station data and gridded data do not agree on the sign of the trend we cannot reconcile the two and make a conclusive statement.

- These consecutive events highlight the broader challenges of managing increasingly frequent and intense hazards in the province, where vulnerabilities are shaped by urbanization, infrastructure inadequacies, and social inequalities.

- As extreme weather events become more common, it is important to keep investing in early warning systems, climate-smart urban planning, and preparedness that takes multiple hazards into account. For instance, creating more green and blue spaces can help reduce heat in cities, provide relief during hot weather, and lower the risk of flooding—all of which can be done even in crowded urban areas.