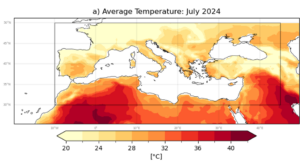

July 2024 saw extreme heat in many countries bordering the Mediterranean, following very high temperatures in Eastern Europe at the start of July. The heatwave occurred after 13 months of extreme heat globally, with each of the last 13 months being the hottest ever recorded. June 2024 was also the 12th month in a row that global mean temperatures have been 1.5C above pre-industrial temperatures. World Weather Attribution published attribution studies on heatwaves impacting the Mediterranean and Europe in April and July 2023.

The Event

Attribution studies continue to show that human induced climate change is making heatwaves hotter and deadlier. In many regions, the influence of human induced climate change is so large that temperatures recorded during heatwaves would not be possible without warming caused by the burning of fossil fuels. This includes parts of the US, the Sahel, West Africa, the Philippines and other countries in East Asia as well as the Mediterranean. We assess how rare the extreme July 2024 heat in the Mediterranean and examine its impacts, focusing on observational data instead of conducting a detailed attribution study, which would likely produce similar results to previous studies. The results are contextualised with findings from our previous attribution studies in the region and global analyses.

Key Messages

- Heatwaves are the deadliest type of extreme weather, with hundreds of thousands of people dying from heat-related causes each year. The July heatwave caused at least 21 deaths in Morocco after temperatures reached 48°C. However, it is likely there were dozens or hundreds of other heat-related deaths in the countries affected that have not been reported and the full impact of a heatwave is rarely known until months afterwards, once death certificates are collected, or scientists can analyse excess deaths. Many places lack good record-keeping of heat-related deaths, therefore global mortality figures are a significant underestimate.

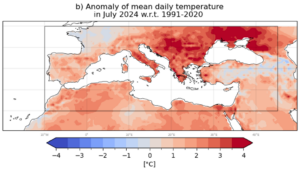

- In line with past climate projections and IPCC reports, extreme heat events like July 2024 in the Mediterranean are no longer rare events. Similar heatwaves affecting Greece, Italy, Spain, Portugal and Morocco are now expected to occur on average about once every 10 years in today’s climate that has been warmed by 1.3°C due to human-induced climate change.

- Based on the data set ERA5, the extreme temperatures reached in July would have been virtually impossible if humans had not warmed the planet by burning fossil fuels. In addition, the 1 in 10 year extreme July heat would have been 3°C [2.5 – 3.3°C] cooler in a world without climate change.

- These results are based on observational data and do not include climate models. However, the results are very similar to the studies published in 2023 that analysed heatwaves in the same region and included climate models. For both the April and e July heatwaves in 2023, we found the events would have been virtually impossible without climate change, but are not rare today. We also found the heatwaves were made 1.7-3.5 ºC hotter when compared to a pre-industrial world.

- The results for the 2023 events synthesised observations and climate models. However, the models are known to systematically underestimate extreme heat in Europe (van Oldenborgh et al., 2022, Vautard et al., 2023, Schumacher et al., 2024) meaning the real world changes due to climate change are probably closer to the changes shown in observations.

- Furthermore, the previous studies use slightly different temporal and spatial definitions of heat, but the numerical results remain very similar. Given the 2024 event is very similar to the observed changes found in studies published 2023, they are a good indicator of how climate change is affecting extreme heat in the Mediterranean.

- Unless the world rapidly stops burning fossil fuels, these events will become hotter, more frequent and longer-lasting.

- Studies show that elite Olympic athletes who are exposed to high temperatures and are not acclimated to them may see impacts such as a decline in performance, and increase in heat-related illness, such as heat cramps and exhaustion, having implications for the Paris Olympics that are currently ongoing (de Korte et al., 2021, Griggs et al., 2019). Measures to reduce exposure, ensure adequate hydration and cooling, acclimatisation, and emergency plans can help keep athletes safe during periods of extreme heat.

- Heat action plans that reduce heat-related deaths are increasingly being implemented across the region, which is encouraging. However, there remains an urgent need for an accelerated roll-out of heat action plans in light of increasing vulnerability driven by the intersecting trends of climate change, population ageing, and urbanisation. Cities are hot-spots for heat risk, so urban planning needs to focus on measures to reduce the urban heat island effect, such as increasing cooling green and blue spaces.