In early January, very cold air masses from the Arctic flowed from the northeast over Northern Fennoscandia, with clear-sky stable conditions allowing the surface to cool further still over a large area. Very low temperatures were measured at several stations/locations, including Enontekiö airport in Finland (-44.3°C on 5 January). On January 6, the cold air mass shifted towards Southern Scandinavia, with a record low reached in Bjørnholt, Oslo (-31.1 °C).

While Fennoscandia is well accustomed to and prepared for winter conditions, very low temperatures have become less frequent in the recent decades and events such as this have the power to surprise and be particularly impactful. Direct impacts of the coldwave will have been felt most strongly by vulnerable groups notably people experiencing energy poverty, living in poor housing stock, and/or experiencing homelessness. Elderly people and children are also more vulnerable physiologically to extreme temperatures. The cold also caused traffic disruptions, school closures, power cuts and infrastructure damage.

Scientists from Norway, Sweden, Finland, France, the Netherlands, the UK and the US collaborated to assess whether and to what extent human-induced climate change has modified the likelihood and intensity of this cold wave.

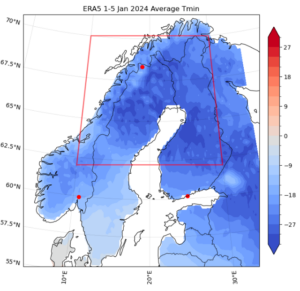

Published peer-reviewed methods were used by the team to analyse the event, on twodifferent scales and locations: Firstly the annual (Jul-Jun) minimum of 5-day averaged minimum temperatures in a region impacted by the onset of the cold wave in Northern Scandinavia, as shown in Figure 1; and secondly the single-day (Jul-Jun) minimum temperature for the station of Oslo, to the south of the study region, impacted slightly later.

Main findings

● Extreme cold such as experienced during this event can have severe direct impacts on health, and secondary impacts on roads, electricity grids, and services such as schools and public transport.

● Cold waves, like other extreme weather events, put significant pressure on energy, healthcare, and water systems. These systems must be designed and able to absorb additional (or different) needs, and early warnings, preparedness plans, and response capacity are all crucial to mitigate the impacts of these events.

● Homelessness in particular, but also energy poverty and bottlenecks with the associated price hikes and, in some cases, poor housing conditions, exacerbate the impacts of cold waves on particularly vulnerable socio-economic and demographic groups.

● Even though some very low temperatures were recorded, the dataset based on observations characterises the area average 5-day cold spell as a 1-in-15 year event in today’s climate, ranking as 12th coldest since 1950. For Oslo, the one day minimum temperature was rare, approximately a 1-in-200 year event in today’s climate.

● To estimate the influence of human-caused climate change on this extreme cold we use a combination of climate models and the observations. We find that because of human-induced climate change the area-averaged event would have been about 4 degrees colder in a 1.2°C cooler climate. This corresponds to such cold spells having become about 5 times less frequent.

● For the Oslo station the cold single day minimum would also have been about 4 degrees colder without human-induced climate change. This corresponds to such cold days having become about 12 times less frequent.

● At global mean temperatures of 2°C above pre-industrial levels, large-scale cold spells as rare as this one are projected to be about another 2.5 °C less cold for the area average and about another 2 °C less cold for Oslo. They will become even less frequent than today.

● Climate change does not mean that cold waves will no longer happen. In fact, less severe and less frequent cold waves may be more impactful than past ones if risk perception and preparedness decrease due to the less frequent event occurrences.