In Bangladesh, Dhaka observed the highest maximum temperature recorded in decades of 40.6°C on 15th April. In India, several northern and eastern cities recorded maximum temperatures above 44°C on 18th of April. Thailand recorded its highest ever temperature of 45.4°C on 15th April in the city of Tak. The Sainyabuli province in Lao PDR reported 42.9°C on 19 April as its all-time national temperature record. Vientiane, the capital of Lao PDR, recorded 41.4°C on 15th April, the hottest day ever for the capital. On the same day, Luan Prabang in Lao PDR reported 42.7°C.

These extreme temperatures, combined with humidity, caused a sudden increase in heat stroke cases, roads melting and a strong surge in electricity demand in all four countries. 13 casualties and about 50-60 hospitalisations due to heat stroke were reported in Navi Mumbai, Maharashtra on 16th of April alone, while other sources mention 650 hospitalisations. Casualties have also been reported in Thailand. The true cost to human lives will only be known months after the event. In India, in the states of West Bengal, Tripura and Odisha, schools closed three weeks earlier than planned due to the heat. In addition, a large number of forest fires occurred during the same time in India, Thailand and Lao PDR.

Scientists from India, Thailand, France, Australia, Denmark, Germany, Kenya, the Netherlands, the US and the United Kingdom collaborated to assess to what extent human-induced climate change altered the likelihood and intensity of the extreme heat in these four countries where temperature records were broken at several locations and harm to lives, livelihoods, and well-being were reported, also due to the accompanying humid conditions.

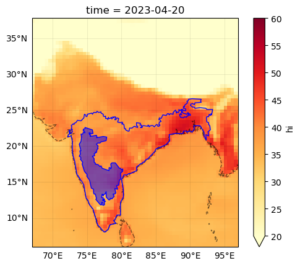

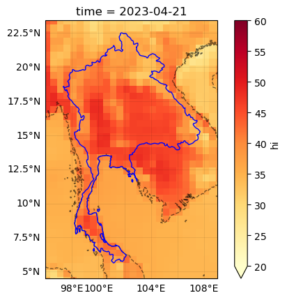

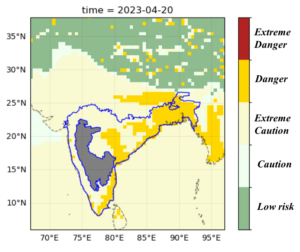

Using published peer-reviewed methods and available datasets, scientists analysed how human-induced climate change altered the likelihood and intensity of the 4-day April heatwave event measured as a heat index that integrates temperature and humidity. Humidity is an important factor in how high temperatures affect the human body, as sweating, the way for humans to cool themselves, becomes less effective at high humidity. Thus, heat is more dangerous in humid conditions. The heat index (reported in °C) takes both temperature and humidity into account. Due to the high humidity conditions during the heatwave, heat index values are higher than the actual temperatures (reported in the first paragraph), as shown in Figure 1. Due to the heterogeneity in climate and landforms over this large area, the team separated the analysis into two smaller homogeneous regions as follows: (1) South and central parts of India and the whole of Bangladesh, excluding the dry, semi-arid region that runs parallel to the Western Ghats where humidity is low in the pre-monsoon season. (2) Thailand and Lao PDR together.

Main findings

- Heatwaves are amongst the deadliest natural hazards with thousands of people dying from heat-related causes each year and many more suffering other severe health and livelihood consequences. However, the full impact of a heatwave is often not known until weeks or months later, once death certificates are collected, or scientists can analyse excess deaths. Many places lack good record keeping of heat-related deaths, therefore currently available global mortality figures are likely an underestimate.

- While people in the affected regions are used to hot and humid temperatures, those who are more physiologically susceptible to heat (e.g. due to pre-existing conditions, age, disability etc.) and/or are more exposed due to their occupation (e.g. outdoor workers, farmers) are at highest risk of heat-related health impacts. Such exposure and vulnerability are intensified by societal disadvantage based on factors such as socio-economic status, religion, caste, gender, migration, and living conditions. On top of this, factors such as air pollution, the urban heat island effect, and wildfires further compound health impacts, particularly among the most vulnerable populations.

- In the current climate, which has warmed by 1.2°C since pre-industrial times due to human activities, the humid heat event (defined using the heat index) is not very unusual over India and Bangladesh, but is estimated to be rare in Thailand and Lao PDR.

- The estimated heat index values exceeded the threshold considered as “dangerous” (41°C) over the large parts of the South Asian regions studied. In a few areas, it neared the range of “extremely dangerous” values (above 54°C) under which the body temperature is difficult to be maintained.

- There is only one data set available for the entire region to calculate the heat index (ERA5). This dataset is known to underestimate extreme temperature trends over India, so the estimates for the rarity and severity of the event are more uncertain than when several datasets can be compared.

- To estimate the influence that human-caused climate change has had on extreme heat since the climate was 1.2°C cooler, we combine climate models with observations. Observations and models both show a strong increase in likelihood and intensity of April humid heat events similar to that of 2023.

- The combined results give an increase in the likelihood of such an event to occur of at least a factor of 30 over India and Bangladesh due to human-induced climate change. At the same time, a heatwave with a chance of occurrence of 20% (1 in 5 years) in any given year over India and Bangladesh is now about 2°C hotter in heat index than it would be in a climate not warmed by human activities.

- Over Thailand and Lao PDR, a humid heatwave with a 0.5% chance of occuring in any given year (1 in 200 years) is now 2.3°C hotter in heat index. An event of the same magnitude as the observed heatwave would have been extremely rare in a 1.2°C cooler climate and hence it would have been virtually impossible to have occurred without climate change.

- These trends will continue with further warming. They are stronger for the rarer event over Thailand and Lao PDR where a heatwave like the recent event would be about 10 times more likely in a 0.8°C warmer world (2°C global warming since pre-industrial times). In India and Bangladesh, the likelihood of this April’s event reoccuring would increase by about a factor of 3 between today and reaching 2°C global warming, meaning that this humid heat event could be expected every 1-2 years.

- There are a range of solutions to heat-related harms from the individual to the regional level. They are currently implemented as a patchwork, to various degrees, across the countries studied, with India having the most advanced heatwave planning. Solutions, such as self-protective action, early warning systems for heat, passive and active cooling, urban planning, and Heat Action Plans can be effective at reducing fatalities and other negative impacts. In fact, heat-related fatalities have decreased in regions where heat action plans have been in place, e.g. in the city of Ahmedabad and the region of Odisha in India. However, these solutions are often out of reach for the most vulnerable people, highlighting the need to improve vulnerability assessments and design interventions that account for group-specific needs.

- High social vulnerability among various segments of society, in combination with the strong increase in extreme heat in the region, is likely to exacerbate the impacts of extreme heat events on those already experiencing substantial disadvantages in their daily lives and hence requires comprehensive adaptation and development interventions.