In mid-February 2025, southern Botswana and eastern South Africa were hit by heavy rainfall, sparking severe flooding across the region. The floods claimed at least 31 lives, including 22 in KwaZulu-Natal (Mhlophe-Gumede, 2025), near Durban, and at least nine in Botswana’s capital, Gaborone, amongst them six children (Government of Botswana, 2025). At least 5,000 people have been displaced. The flooding across the border between Botswana and South Africa, caused by heavy rainfall from the 16th to the 20th of February, wreaked havoc on both countries, shutting down major ports of entry into South Africa, forcing the temporary closure of all government schools in Botswana, and causing widespread traffic chaos. Many areas became completely cut off, leaving residents stranded and emergency services scrambling to respond to the aftermath.

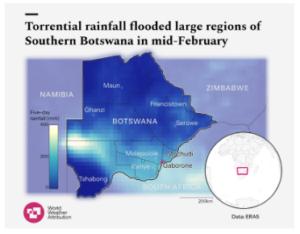

To assess whether and to what extent human-induced climate change altered the likelihood and intensity of the heavy rainfall leading to the flooding and what other factors in vulnerability and exposure played an important role in driving the impacts, scientists from Botswana, South Africa, Denmark, Mexico, Austria, Sweden, the Netherlands, the United States and the United Kingdom, studied the event as depicted in figure 1, focussing on the 5-day maximum rainfall in the region with the most severe impacts.

Main Findings

- During the rainy season Gaborone and other urbanised areas frequently experience flooding. High-intensity rainfall overwhelms drainage systems, often leading to significant urban flooding. The capital city’s drainage infrastructure has not kept pace with its growing population density and rapid urbanisation rendering low-lying areas particularly susceptible to severe flooding events.

- Even in today’s climate, which has warmed by 1.3 °C, the 5-day heavy rainfall event observed in February 2025 is relatively rare, expected to occur only once every 10 to-200 years, depending on the source of data. We use a 50-year return period for the remainder of the study. Analysing weather station data for Gaborone we find that the event has a return period of 40 years, meaning it has a 2-3% chance of occurring in any given year.

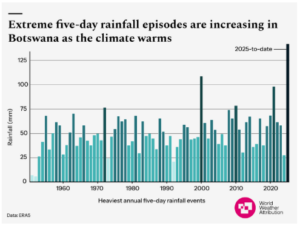

- To assess if human-induced climate change influenced the heavy rainfall in the region, we first determine if there is a trend in the observations, available since about 1950, that aligns with the pace of the earth’s warming. Results show that observed 5-day rainfall events like that in February 2025 would have been much less likely to occur in a colder climate. Extrapolating this trend back to a 1.3 °C colder climate, this increase in intensity is estimated to be about 60%.

- To quantify the role of human-induced climate change we also analyse climate model data over the relatively small study region for the historical period. Overall, the available climate models show very different results. Some show a large increase in the frequency and intensity of extreme rainfall events, as in the observations, others show no change or even a decrease. This might be a result of climate change forcing in the models being comparable in strength with natural variability. Thus we cannot precisely quantify the role of climate change.

- When looking at a 2.6 °C warmer climate compared to preindustrial (the level of warming projected to occur later in the 21st century) we find that the majority of models show an additional increase in the magnitude of 5-day heavy rainfall events relative to 2025. This indicates the emergence of a climate change signal under higher warming levels.

- Taking together: (1) the very strong historical trend in all observed datasets; (2) the fact that warmer air can hold more water vapour which leads to a potential increase in rainfall intensity, and (3) the shift towards an increase in the majority of models with future warming, we conclude that human-induced climate change amplified the rainfall leading to flooding in southern Botswana, but cannot confidently quantify by how much.

- Considering that the majority of impacts of the February extreme weather event occurred due to flooding in urban areas, and that flooding often occurred historically, even under less extreme events, it is highly likely that those impacts were magnified by infrastructure not built to withstand such extreme rainfall. Roads, drainage channels, and dams were overwhelmed, while health clinics (e.g. in Molapowabojang and Kanye) faced severe disruptions.

- There are ongoing efforts to strengthen flood resilience through improved drainage, land-use regulation, and disaster preparedness. Expanding drainage capacity, enforcing zoning to limit development in high-risk areas, and upgrading critical infrastructure to withstand both present and future climate challenges can further enhance resilience. A comprehensive approach that integrates multi-hazard assessments into urban planning, infrastructure development, and disaster preparedness, along with stronger early warning systems, can improve resilience to future extreme events.